Discovering the diversity and breeding origin of Black-tailed Godwits in Bangladesh

Black-tailed Godwits (Limosa limosa, hereinafter: godwits) are commonly seen in coastal and freshwater wetlands of Bangladesh. They do not breed in Bangladesh but migrate here to spend their non-breeding period. But from what breeding areas do Black-tailed Godwits migrate from to Bangladesh? We know godwits breed over a vast area in the northern part of the world, from Iceland in the west to the far east of Russia. Based on their fragmented breeding locations, four distinct breeding populations (subspecies) have been identified, namely limosa, islandica, melanuroides, and bohaii. But which of the four subspecies travel to the wetlands of Bangladesh? Do they migrate along the coast or do they migrate over the mighty Himalayan Mountains? All unresolved, but highly interesting questions, not in the least because of the geographical characteristics and position of Bangladesh.

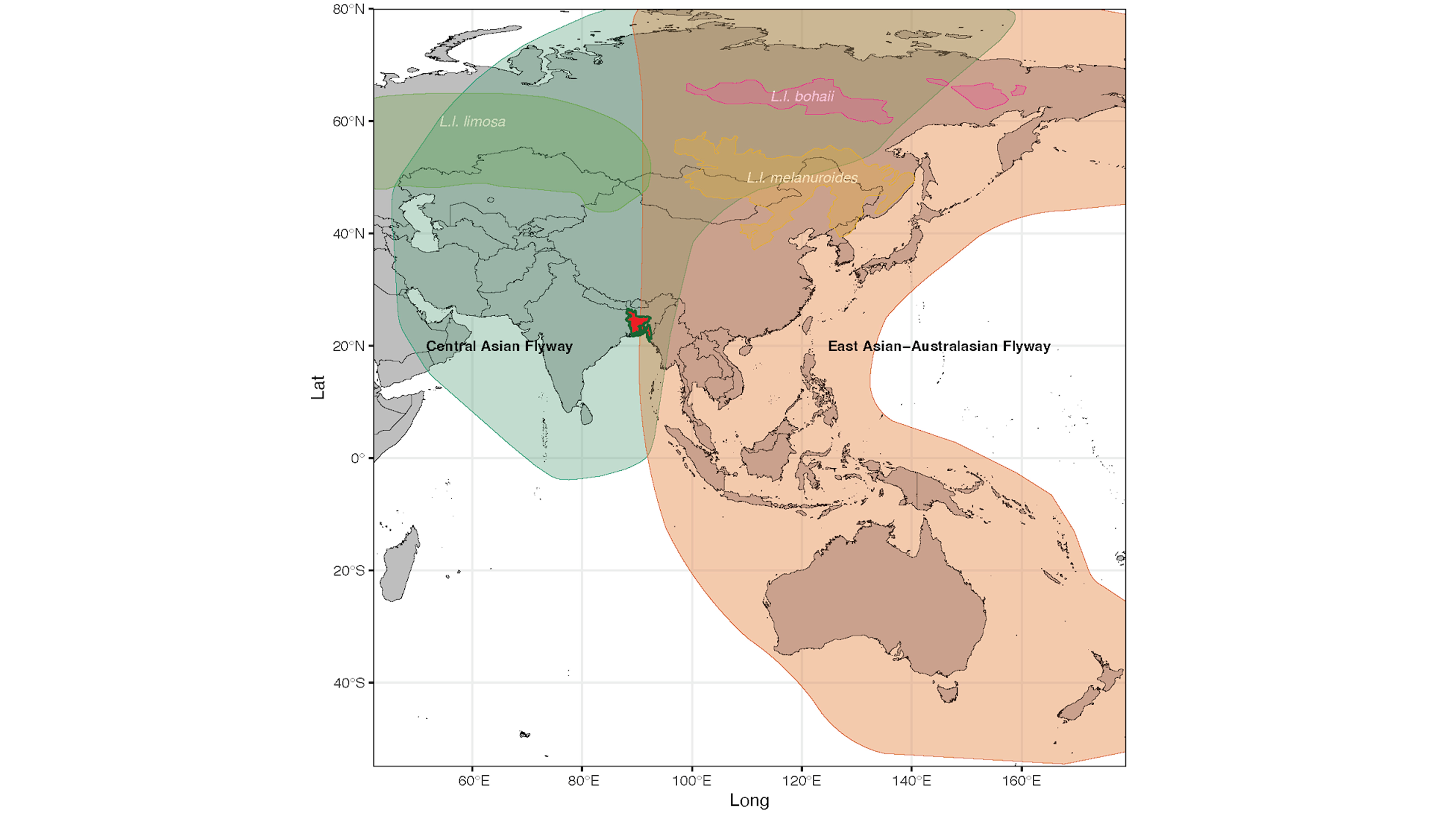

Bangladesh is a lowland located in the largest river delta of the world, the Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna Delta. The mighty Himalayan Mountain stands as a high wall in the north of the country and the majority of its waters drain to the Bay of Bengal through Bangladesh. From a shorebird perspective, Bangladesh lies at the overlap between the Central Asian and East Asian-Australasian flyways, suggesting birds from very different breeding populations could co-exist here during the northern winter. From a godwit perspective, the question of which subspecies occur in Bangladesh became more interesting with the recent discovery of the bohaii subspecies in Asia by Bingrun Zhu.

Size difference between individuals is one of the main indicators that differentiates four subspecies of Black-tailed Godwits. And I observed substantial size differences between individual godwits in Bangladesh, even between birds in the same flock. These observations, combined with the position of Bangladesh between two flyways, indicate it is likely that multiple subspecies migrate to the largest delta country to spend their non-breeding time. So for my PhD research, I have taken on the mission to solve this puzzle.

In the past two winters I captured godwits from two sites in Bangladesh, Nijhum Dweep and Tanguar Haor, allowing me to take detailed body measurements, collect blood (DNA) samples to confirm their subspecies, and to deploy satellite trackers to track their migratory movement. By now, I have finished genetic analyses that confirmed three subspecies co-occurring in Bangladesh, and am currently writing up a first manuscript detailing the subspecies composition at each of my study sites, and comparing the biometrics of these birds with previously published data. Meanwhile, our tracking data is showing that Bangladeshi godwits make trans-Himalayan migrations to a wide range of areas from Kazakhstan in the west to China in the east. But this is just the tip of the iceberg, and I look forward to dig much deeper into the migration routes and behaviours of godwits in the understudied Asian flyways.

On Wednesday November 8 Delip’s co-supervisor Prof. Mostafa Feeroz will publish a short documentary about the Black-tailed Godwit research, featuring some gorgeous images of godwits and fieldwork in Bangladesh.

It will be available from November 8 onwards, here.